Read my article for the Times below or access it here.

Fifty-one years ago the United Kingdom signed up to the UN Genocide Convention, designed to ensure that atrocities like those that happened during the Second World War could “never again” take place.

Yet since then at least half a million people were killed during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, over a million died in the genocide in Bangladesh in the 1970s, 1.7 million people lost their lives in the Cambodian genocide and we have witnessed appalling atrocities by Daesh [Islamic State] against Christians, Yazidis and other ethnic and religious minorities in Iraq and Syria. So why has this landmark treaty done so little to stop atrocities from happening?

Because there’s a vicious circle at the heart of the international legal order which has meant that successive UK governments have found it impossible to act in the face of genocide.

The UK position has always been that the government can only define an incident as a genocide if this has been determined in the International Criminal Court (ICC). The only way anything gets to the ICC is if the UN Security Council sends it there, and China and Russia have the power to veto anything the UN Security Council does.

And this is especially important today given that in China, two million Uighurs and other minorities are being forced into slave labour prisons and camps in Xinjiang’s cotton fields. The horror of mass enslavement of the Uighur continues with state-organised violation and abuse of women and girls who are facing forced sterilisations and a resulting 85 per cent drop in Uighur birth rates. This is a key marker of the UN’s definition of genocide.

Yet our country’s capacity to respond is being handcuaed once again by geopolitics and the fate of so many people depends on Britain playing a leading global role in breaking the logjam.

We have now left the EU and taken back control of our laws and our trade policy so that we can reach out to new trading partners, including some of the fastest growing economies in the world. And never have we needed these freedoms more as we recover from the economic eaects of Covid and the government’s response to it. But with this freedom comes both opportunity and responsibility.

An opportunity to use our new independent trade policy as a tool with which to do good — both for our own citizens and people all over the world — and to demonstrate the values global Britain wants to live up to.

Brexit wasn’t a vote for Britain to pursue isolationist policies, to pull up the drawbridge or to downgrade our values. It was a vote, full of hope and optimism, which said that Britain should play its part in leading the global world order, rather than having the EU set our values for us.

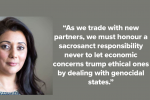

So as we form trade deals with new partners, we must honour our sacrosanct responsibility never to let economic concerns trump ethical ones by dealing with genocidal states. If a country is mired in genocide — the crime above all crimes — Britain must not be complicit.

So I am supporting a small but significant change to the government’s trade Bill. Rather than say genocide is a matter for international law, knowing full well that it is paralysed by global politics, this amendment gives British courts a role instead. This is one of the many benefits of taking back control of our own laws and will ensure that the government’s longstanding policy will actually mean something.

If a UK court has seen credible evidence that the crime of genocide is being committed, judges will be able to make a statement to that eaect for the government to consider.

It wouldn’t tie the hands of the government — that would be unconstitutional. The government could, if it wished, choose to ignore it, and the courts wouldn’t be able to strike down trade deals or laws. But why on earth wouldn’t the government want to know if a genocide is being committed in a state it was discussing trade with?

Governments around the world have been slow to act. We don’t need more bureaucracy, tokenism, impact assessments or vague and wady virtue signalling nonsense that doesn’t achieve anything. Britain must aerm the principle that we will never trade with countries that commit genocide, and nor will we look the other way or do business with its perpetrators. Genocide cannot mean business as usual.

As we herald a new dawn with President Joe Biden, and as the UK takes on the presidency of the G7, Britain can blaze a trail and provide leadership to the world, stand by the international rule of law and promote our hard won values and standards.

In the 75 years since the Nuremberg trials, the UK has never succeeded in recognising a genocide while it was ongoing. We now have a chance to put that right.